Testing with Create React App - Part 1

Testing your code

There are a great many articles, books, and test-driven development evangelists who will argue the case for why you should have an automated test suite. This is not another one of those articles.

This is my practical journey into automated testing as part of a Covid-19 lockdown project to try out TypeScript with React.

This is not a blog post on why you should use TypeScript either. As with automated testing, there are a great many articles that explain the benefits of using TypeScript far better than I could.

Well, maybe a little preaching...

I'll keep it short.

Why TypeScript?

- Static typing is a good thing.

- It's verbose for sure, but rules out a whole subset of potential bugs when building complex JavaScript applications - Which, I would argue, even small React applications qualify!

- Because TypeScript is statically typed and has things like interfaces and custom types, it allows us to (hopefully) build more robust, and agile applications.

Why automated testing?

For me, the way I tend to code is to laser focus in on what I'm doing to the point of not fully checking all other aspects of a project while I'm hacking up a portion of the codebase. With an automated test suite, I can be fairly confident that I've not severely broken some other part of the codebase when making changes.

I also try to clean up and refactor my code when I've got something working so that my future self in 6 to 12 months will not hate my current self too much. With an automated test suite, you can be fairly confident that your refactorings have been a force for good and have not introduced any new bugs.

I want to point out the use of "fairly confident" above. Automated testing does not mean that you just fire-and-forget code so long as your tests pass. Have a quick test yourself once in a while - test your tests!

Testing has allowed me to keep on trucking knowing that I'm probably on the right route and not drifting into oncoming traffic while I fiddle about with the radio.

Setup

If you're using Create React App then you've already got out-of-the-box testing with Jest. With the basic skeleton project setup you'll already have a file called App.test.{jsx,tsx}, depending if you're using TypeScript, which will contain a single test to ensure that your application will render without failing.

To run your tests, depending on your package manager of choice, you need to run:

yarn testor

npm testYou should get a passing test (if your application isn't already bugging out).

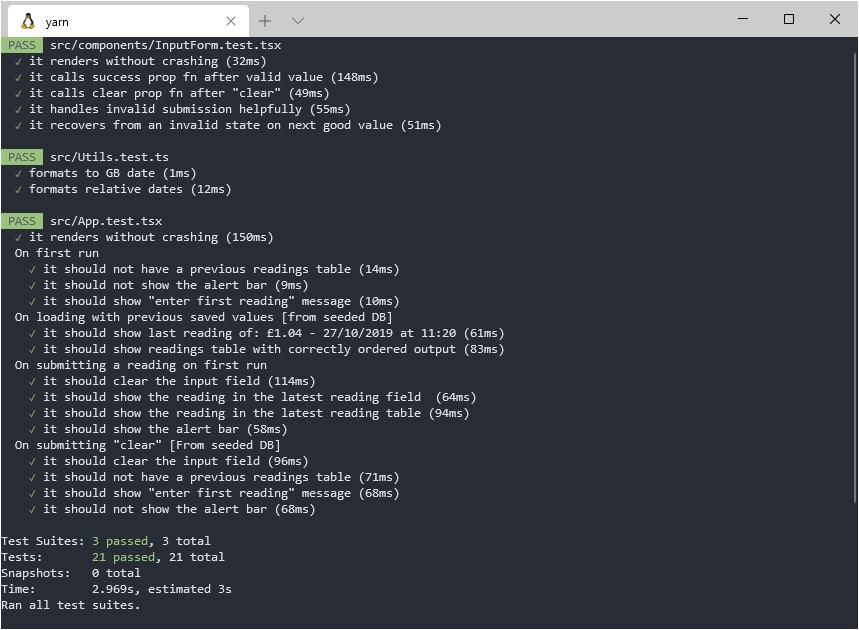

PASS src/App.test.tsx

✓ it renders without crashing (148ms)If you do not see the above then it's time to sharpen up those googling skills!

OK, cool-cool. Now what?

Good question. That's not easy. Some people will say that you should test every line of code in your project and gain 100% code coverage. While others say test what matters most - in other words, test the complicated bits.

For now, I'm testing the more nuanced pieces of my project as they're most likely to cause problems. 100% coverage is the end goal though.

Testing lingo

To help yourself when diving into tutorials or looking for things, you'll be better served if you speak the language of testing.

You write unit tests. A unit test is a test that tests a unit - of code.

In other words, if you have a function, you write a test for that function. With Jest, we can also create groups of unit tests. A bunch of single, or grouped, unit tests forms a test suite. A test runner then runs all test suites.

General project structure

You'll likely have one test file per code file. That test file is the test suite for that code file.

In the test file, you'll have one or more unit tests per function you want to test.

In the unit test, you'll have some assertions to make sure the code is behaving as predicted. For example, the "Hello, World!" of testing:

//File: Calculator.js

const add = (a, b) => a + b;

//File: Calculator.test.js

test('its not 1984', () => {

expect(add(2,2)).toBe(4);

expect(add(2,2)).not.toBe(5);

});These lines beginning with expect are assertions. An assertion is saying we expect that the code under test will produce what we think it should.

expect(ourCode).toMatch(ourPrediction)If those assertions pass, the unit test passes. If all the unit tests pass, the test suite passes and you can call it a day and clock off ear... I mean, refactor your code some more.

Check out the jest documentation for more assertion matchers.

Other testing practices

We're going to cover unit tests in this and the next blog post. You can also get end to end tests, integration tests, and acceptance testing.

Baby steps

The first thing I did was to take a small custom date module that is responsible for printing human-friendly dates on my app and started to write tests for that as it seemed easiest to get going with. We'll cover testing React components in the next post.

For example, I have a function that takes a date in yyyy/mm/dd hh:mm:ss formatted string and returns an object with the component parts. Here's my unit test for that:

//File: Utils.test.ts

import {getDatePieces} from './Utils';

test('it splits a date into the right pieces', () => {

expect(getDatePieces('2020/02/01 09:08:00')).toEqual({"y": "2020", "m": "02", "d": "01", "h": "09", "i": "08"});

expect(getDatePieces('2020/02/28 09:08:00')).toEqual({"y": "2020", "m": "02", "d": "28", "h": "09", "i": "08"});

});When you run Jest (or any test runner) you'll get the following (or comparable) output if your test passes:

✓ it splits a date into the right pieces (1ms)Or if something goes wrong:

✕ it splits a date into the right pieces (6ms)

● it splits a date into the right pieces

expect(received).toEqual(expected) // deep equality

- Expected

+ Received

Object {

- "d": "01",

+ "d": "02",

"h": "09",

"i": "08",

- "m": "02",

+ "m": "01",

"y": "2020",

}(I swapped my days and months around)

Lets again examine this line:

expect(getDatePieces('2020/02/01 09:08:00')).toEqual({"y": "2020", "m": "02", "d": "01", "h": "09", "i": "08"})I like this because if I had stumbled on this test without seeing the code I would, just by looking at this test:

- Know the function takes a date string

- Know that date string should be formatted in

yyyy/mm/dd hh:mm:ss - Know I get an object literal as a return value

- Know the full properties of that object - no

console.logrequired! - Know thtat the values are zero-padded, e.g '02' instead of '2'

That's a lot of code knowledge for a single line!

For comparison, here's the code:

/**

* Given date string, returns zero padded values

*

* Returns object with PHP style date pieces: h - hour, i - minute

* @param dateString string - parsable date string

*/

export const getDatePieces = function(dateString: string){

const date = new Date(Date.parse(dateString as string));

let d:any = date.getDate();

if(d < 10){

d = `0${d}`;

}else{

d = `${d}`;

}

let m:any = date.getMonth() + 1;

if(m < 10){

m = `0${m}`;

}else{

m = `${m}`;

}

let h:any = date.getHours();

if(h < 10){

h = `0${h}`;

}else{

h = `${h}`;

}

let i:any = date.getMinutes();

if(i < 10){

i = `0${i}`;

}else{

i = `${i}`;

}

const y:any = `${date.getFullYear()}`;

return {

d,

m,

y,

h,

i

};

};That code, doesn't look so hot right? One quick refactor later with a run of the test suite on file save:

/**

* @typedef {Object} DatePiecesObject - broken down date object

* @property {string} d - day

* @property {string} m - month

* @property {string} y - year

* @property {string} h - hours (24)

* @property {string} i - minutes

*/

type DatePiecesObject = {

d: string;

m: string;

y: string;

h: string;

i: string;

};

/**

* Given date string, returns zero padded values in object form

*

* @param {string} dateString - parsable date string

* @returns {DatePiecesObject} parsed date in zero-padded object

*/

export const getDatePieces = (dateString: string): DatePiecesObject => {

const date = new Date(Date.parse(dateString));

return {

d: `${date.getDate()}`.padStart(2, '0'),

m: `${date.getMonth() + 1}`.padStart(2, '0'),

y: `${date.getFullYear()}`,

h: `${date.getHours()}`.padStart(2, '0'),

i: `${date.getMinutes()}`.padStart(2, '0'),

};

}; ✓ it splits a date into the right pieces (1ms)Much nicer! Job Done - let's call it a day.